The Strange Loop That Makes Us a Self.

Where Does the "I" of ME Live?

Happy Wednesday, friend!

You are reading The How to Live Newsletter: Your weekly guide offering insights from psychology to help you navigate life’s challenges, one Wednesday at a time.

Donating is Advocating

This newsletter is a free mental health resource, but it requires significant time and financial investment to produce each week. If you've gained wisdom or insight from these newsletters, please consider making a donation or upgrading to a $6/month subscription. Your patronage has an enormous impact and makes a real difference in keeping this resource paywall free. 🙏🏼❤️

What is a Self?

Were we to be taken apart surgically, there isn’t a doctor in the world who would be able to locate this thing we call “I.”

We can’t capture it under a microscope or prod it during surgery.

The “I” of us, the “self” of me, isn’t concrete or tangible, and yet we are all, to varying degrees of consciousness, trying to grow, tame, avoid, hurt, help, and even nurture it.

But what and who are we caring for?

Who is this “I” we always speak of?

Where does the “I” of me actually live?

When we refer to ourselves, we use the names our parents chose for us, names that represent this supposed “I,” but our bodies are not who we are.

They are mere physical vehicles that allow us to contain and transport our organs from one place to another without spillage.

We constantly mistake the bodies of us for the “I” of us. This is what we humans are known for—misapprehending as real all that is phantom.

Take God for instance.

Or, a better, less polarizing example, my favorite topic: Emotion.

When we are anxious, we mistake the sensations of dread and fear inside our bodies to mean that something is dangerous.

We confuse our somatic waves of worry that someone hates us, or that we’re getting fired, or any number of things, for fact.

But feelings are not facts, no matter how real the feeling.

Many people find themselves trapped in silent competitions against their peers using arbitrary measures, plotting their achievements and failures onto an invisible chart that they believe is who they are.

But we are not our measurements, and if we are not our test results, or the measure of our outsize emotions; if we are not our bodies or even our brains, what, then, are we? And where are we?

Some people—take me, for instance—spend decades tracing the roots of their present-day behavior back to specific origin points, precise moments that might help them finally understand why they are the way they are; and people like me do this so that we can break the cycle and reclaim the original self we feel we were meant to become, an original self that existed before the world had its way with us.

So much work is devoted to untangling the Gordian knot of self with nary a thought given to the actual self.

What is a "self," and how exactly did our capacity for awareness arise from matter seemingly incapable of awareness?

Two Birds M.C. Escher Date: 1938

When a system of “meaningless” symbols has patterns in it that accurately track, or mirror, various phenomena in the world, then that tracking or mirroring imbues the symbols with some degree of meaning—indeed, such tracking or mirroring is no less and no more than what meaning is.”

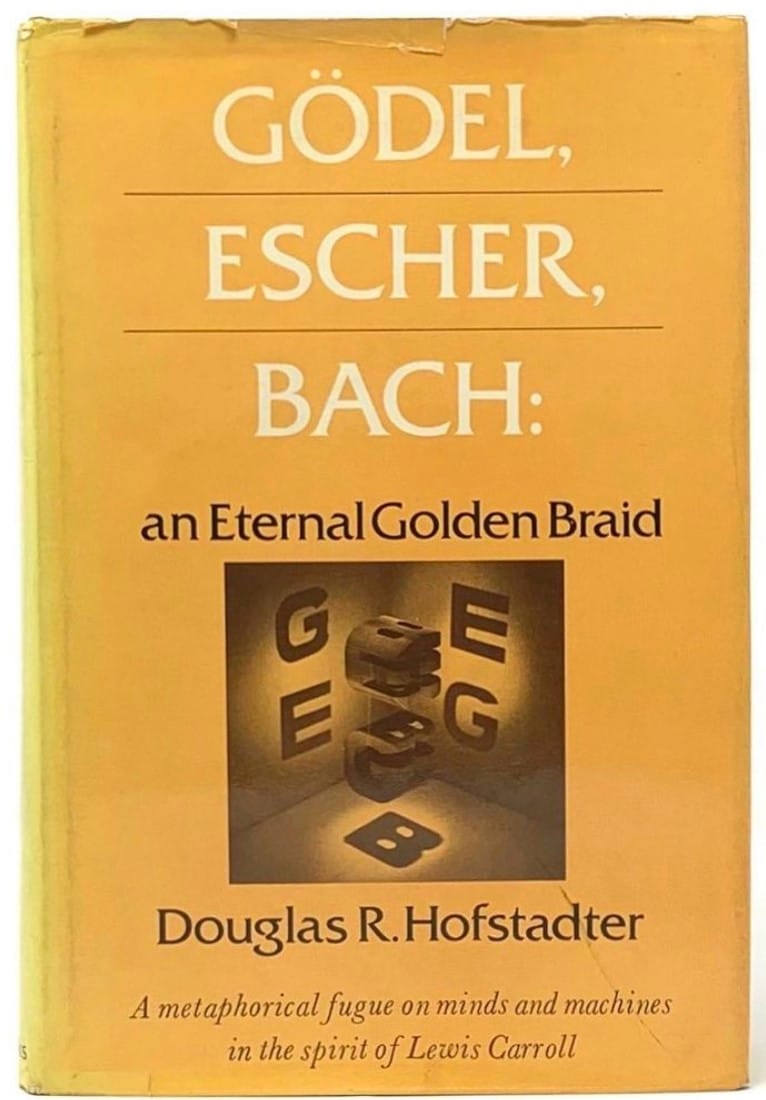

In his 1979 Pulitzer Prize–winning book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. Douglas R. Hofstadter, an American cognitive and computer scientist, explores this very question.

How do meaningless things become meaningful? We are made up of molecules, carbon atoms, and proteins, and yet none of these things have an “I.”

How is it possible to get an “I” out of something that has no “I”?

It’s not therapists who have solved how to derive meaning from meaninglessness, but—Hofstadter believes—mathematicians.

When a mathematician assigns arbitrary symbols to an equation in order to answer a question, they are linking the arbitrary symbols to the question itself.

If X=table then X and table are the same.

We’ve gone from a meaningless symbol to something that refers back to itself, and it’s that self-referential nature that gives a thing its meaning.

The meaningless symbol and the self-reference that arises from that meaningless symbol is—mathematicians claim—equivalent.

This self-reference in equations is a recursive loop. It’s a self looking back on itself, and in so doing, it becomes self-aware; this is how an established system acquires a self.

That loop is a pattern, and it’s this very pattern that is the signature mark of having a self. In Hofstadter’s view, the “I” arises through the brain’s mirroring pattern. Patterns in the brain mirror the brain’s mirroring of the world, which then mirrors itself, creating a causal form that becomes the “I.”

Douglas Hofstadter posits that we are, each of us, all just strange loops. What we see and our interpretation of what we see is no more—and no less—than our own projection onto external material. In order to understand these projections, we ascribe them meaning and then register that meaning as our own perception.

The “I” inside of us manifests itself as the “I” we project and perceive in the world, and our experience is the experience of ourselves, tossed out and absorbed back, like looking in a mirror. Our sense of the world is a mere projection of our self onto signs and symbols, which acquire meaning that we provide.

If this is the case, then the “I” of ourselves, and how we interpret what we see, is never actually outside of ourselves. When we are speaking to a friend, we are really speaking to ourselves inside the body of another.

And if we are mere projections of the person viewing us, then aren’t we all just replicas of the people who raised us, and they of the people who raised them? We look outside to understand who we are, but if what we are looking at is only ourselves projected outside, then who, or what, is the “I” inside?

Deepak Chopra, a physician, author and alternative medicine advocate, has a similar view of the self, which is essentially that we create our own world because we can only see from one perspective.

We see with our own specific sadness, our joy and sorrow, with our anxiety and insecurity.

And certainly, there are moments where we are free from that, but does the world make as big an impression on us when it’s not fraught or heightened in some capacity?

And what of “I”?

A single letter suggesting a single definition, but “I” cannot be just one thing, and to answer the question, “Who are you?” isn’t possible or even fair, as we don’t and perhaps can’t ever know all that we are, as much as we might know all that we aren’t, and so to write about oneself as though you know the answer to “I” is as false as claiming you know God, or you know what made the world.

We can only guess.

To say who you are is to offer ideas.

We are patterns that we’ve made to mean something.

We think we know who we are, but most of us are wrong—who are we really but the internalized stories of ourselves that other people tell?

Among those who proclaim to know that they’re this way or that, what they can and can’t do, buy into the story of themselves that’s not even their own, didn’t even know they’ve been living—but underneath, or over to the side, maybe even high up, there, is where a different self-state exists—one you think isn’t you, but it is, it’s just an unfamiliar part of yourself, like the part that couldn’t swim before you learned, couldn’t sound out words you didn’t yet know.

Once, you didn’t know, and then you did.

That once part exists still for other things, but just because it’s not familiar doesn’t mean it’s not you.

@millardmendez from Instagram

We tell our own story because we believe it, and hope others do too, and even if somewhere in us a chime of doubt sounds, this doesn’t make us liars, it just means we’ve no reason to doubt what we say is true, but words don’t tell the story, action does.

And this is where things get really uncomfortable, because knowing yourself and telling about yourself involves more than reconstructing what’s happened to you, what you’ve dealt with, and even what you’ve learned, it’s beyond what people did to you or how you suffered or overcame; the thing that people overlook in their own self-assessments and narratives is the grief they have caused others, how they have helped or harmed those in their path.

The pain we’ve inflicted is also who we are and one cannot truly assess their own “I” without looking at their actions, which means seeing yourself from someone else’s vantage point.

Just like you, there’s a very tiny crack in me where the “I” is stuck, as if caught between two teeth.

We can accept Hofstadter’s theory, or Chopra’s—or neither.

Whomever or whatever you decide to believe, what’s important is that your “I” is, more than anything else, an experience, one you can’t control, but from which you can always create meaning from the meaningless symbols.

What is YOUR “I” of self? Let me know in the comments!

Until next week I will remain…

Amanda

PS. Feeling overwhelmed? Soothe yourself by making your own repeating pattern of polygons, like Escher’s painting, with this Interactive Tessellation Website!

VITAL INFO:

Nope, I am not a licensed therapist or medical professional. I am simply a person who struggled with undiagnosed mental health issues for over two decades and spent 23 years in therapy learning how to live. Now, I'm sharing the greatest hits of what I learned to spare others from needless suffering.

Most, but not all, links are affiliate, which means I receive a small percentage of the price at no cost to you, which goes straight back into the newsletter.

💋 Don't keep How to Live a secret: Share this newsletter with friends looking for insight.

❤️ New here? Subscribe!

🙋🏻♀️ Email me with questions, comments, or topic ideas! [email protected]

🥲 Not in love? 👇

Join the conversation