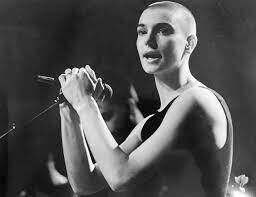

This Is To Mother You: The Life and Death of Sinead O’ Connor

Our Problem With "Unlikable" Characters

Hello friends,

Did you miss last week’s newsletter? It was a biggy.

On July 19th, after 23 years with the same person, I ended therapy.

I’m keeping notes on life in the immediate aftermath, so perhaps I’ll write about that soon. In the meantime, this week is about Sinead O Connor and what, if any, responsibility an audience bears.

She meant a lot to me.

Become a member to engage more deeply, find your people, and build community in real-time. Click Upgrade to see what’s included.

Prefer to skip the membership offerings and donate? You can do that, too. Every donation helps support the hundreds of hours I spend every month researching, writing, and finding the most useful content to help ease your suffering and feel less alone.

This Is To Mother You: The Life and Death of Sinead O’ Connor

In my 20s, I lived in NYC’s East Village, on St. Mark’s between 1st and A. My boyfriend was a talented musician. He played all over the village and knew as much about new bands as the next East Village musician, but the person who knew my taste best ran a music store on 7th Street. The store was Stooz Records, and the person who often changed my life was the owner, Stu.

That was a tear-soaked decade. I was constantly unglued, as many are in their 20s—especially those with undiagnosed mental illnesses.

I was always looking for something to cry to.

Stuck and wedged in my rib cage was a limitless trapped sob best released by the right song. Ever the producer, I was always curating my tears.

Once or twice a week, I’d wander into the record store to look, but inevitably, Stu would hand me a new cd, and I’d race home and listen, hoping a song would release my stuck grief.

And every time, there was always one song that would and it made it onto my growing Music For Crying Playlist.

Before they were ubiquitous, Stu introduced me to The Cranberries, Bjork, Beth Orton, Portishead, Hole, and Sinead O Connor.

Sinead O Connor was the musician whose songs helped me cry the most. Gospel Oak just did me in.

I needed her help to dislodge my feelings, and she helped me.

It would take many years for me to realize she also needed help, and none of us did for her what her music did for us.

As I got older and watched celebrities disassemble in real-time, I was horrified that paparazzi would race forward, not to console, but to capture and profit from the clear suffering of their fellow human beings.

I have long wondered what responsibility—if any—the public bears when celebrities, in clear emotional danger, come unglued in public or their art.

Art is often made from and about the depths of emotion—joy, and anguish, and we eagerly pay to consume their output. We grow close to their work, but when the artist falls apart, we quickly demonize them.

Sinead O Connor was 25 years old when she appeared on Saturday Night Live and tore a photo of Pope John Paul II to bring light to the horrific sexual abuse of children in the Catholic Church.

This wasn’t an act of mental illness. It was an act of defiance performed by someone who happened to suffer from mental illness.

While many embraced her, there were more who condemned her. They either didn’t understand her warning or didn’t care; she was swiftly canceled.

A week later, when Joe Pesce hosted, he said, “She was very lucky it wasn’t my show, because if it was my show, I woulda gave her such a smack…” (audience laughter and applause) “I woulda grabbed her by her—(he reaches up to his hair) eyebrows…”

Sinead O Connor was alerting us to violence against children, and she was canceled. Joe Pesce was threatening violence against a woman, and he was celebrated.

By the time she appeared on SNL, she’d already angered many by defiantly standing up for her beliefs.

Months earlier, she’d performed at the Garden State Arts Center in New Jersey (now called PNC Bank Arts Center), which begins every show with the National Anthem. O’Connor banned the anthem from her most recent show.

This offended people, so the following night, Frank Sinatra told the audience he wanted to meet her so he “could kick her.”

Radio stations banned her.

She refused to participate in the Grammy Awards in February of the year before. She wrote to the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences president, Michael Greene, telling him, “I don’t want to be part of a world that measures artistic ability by material success.”

She found it insulting that the most sold records are considered the best.

In a letter to the Grammys, which she pulled out of in 1991, she writes:

As artists, I believe our function is to express the feelings of the human race—to always speak the truth and never keep it hidden even though we are operating in a world which does not like the sound of the truth…

I believe that our purpose is to inspire and, in some way, guide and heal the human race, of which we are all equal members…

We are allowing ourselves to be portrayed as being in some way more important, more special than the very people we are supposed to be helping—by the way we dress, by the cars we travel in, by the ‘otherworldiness’ of our shows and by a lot of what we say in our music.”

Read the full letter here:

By the time she appeared on SNL, she’d already violated expectations of conformity, gender, and behavior.

Sinead O Connor was a protest singer. She was a punk who stood by her beliefs, adamant in thwarting mainstream music’s expectation that she girl herself up and be good.

We didn’t understand her because we’re conditioned to turn our backs on people who challenge and defy our expectations. When we don’t understand something, we are not encouraged to see through a different lens or investigate what we don’t know.

When people challenge or defy our expectations of them, we are disappointed. When celebrities do it, we are outraged. When women refuse to conform to gender stereotypes and hetero-normative behavior, they are branded “Crazy.”

Sinead O Connor was considered “Crazy.”

She sang about it, and we consumed and sang along, but we did not listen; we chose not to hear her.

Take these lyrics from “Red Football.”

Sinead O Connor’s mother physically and emotionally tormented her as a child. Like most people who suffer terror and harm at a young age, she spent her life warning others about predators hiding in plain sight, seeking to protect children from suffering, and the public shamed her for it.

Child abuse is an identity crisis and fame is an identity crisis, so I went straight from one identity crisis into another.”

And when she tried to call attention to child abuse through her fame, she was vilified.

We treat celebrities like they are products, mobile brands, lacking the human emotions we all share.

When we love their work, we celebrate them and revel in their mastery, but when they disappoint us and behave in ways that defy explanation, we castigate them. We chase them like prey, eager to capture them in disrepair, package and sell them in tabloids across social media, and dissect them as though we know them personally.

We exalt and then ruin.

We consume their music, listening to the lyrics we need to feel less alone or understood, but rarely do we ask or wonder who is helping the person who wrote the lyrics that help us?

Take the song that I used to cry. Here are some lyrics:

We take “You” in the lyrics to mean us, but she’s singing about abused children; she’s singing to herself as a child as much as she’s singing to them.

We take lyrics like this personally and feel a connection, and then when our artist does something we don’t like, we take that personally also.

Upon feeling betrayed, we betray.

We ascribe meaning to behavior we don’t understand; we fill in the blanks with fiction and then punish based on the story we’ve told.

We do this again and again. Rarely, if ever, do we learn from our mistakes or the misfortune of others.

Why do we love to languish in the pain of celebrities who suffer? Before they suffered in public, we envied and wanted their talent. Still, when they disappoint us, we no longer want any of it and feel betrayed somehow, and we want to distance ourselves as though their misstep or protest affects us personally.

In O’Connor’s case, I believe a large part is misogyny, but I think there’s another aspect of it.

Here’s my theory:

People have trouble relating to the worst in themselves.

Take, for instance, audiences who are quick to dismiss movies or books due to “unlikable characters.”

In life, we chafe most at the annoying characteristics and behaviors in others because it reminds us of our own; it hits too close to home.

When we accept all aspects of ourselves, including the unlikeable bits, we aren’t threatened when we hear our echoes in others.

When we are disconnected from the parts of ourselves we don’t like; we are quick to dismiss all representations of these characteristics in others because we are afraid or simply unready to relate.

This is one reason for punishing or canceling celebrities who reveal what we deem the worst of themselves. We quickly punish others for being too human, authentic, and vulnerable. When we can’t handle change or disruption in our lives, we are threatened by waves others make that ripple too close to us.

To be clear—I am not talking about people who cause harm to others, I am talking about people who cause harm to themselves because they are in pain or are warning us of someone else’s pain, and we stand back and cause them further agony.

But what can we do?

What is expected of an audience? Anything? Nothing? How can we reconcile actively supporting someone’s work while being passive about their mental health?

Leave your comments. I look forward to hearing your thoughts.

Liked this?

In the meantime, here is my crying playlist, with all of the 90s songs and some new ones…

About me: I am an author and a mental health advocate. I’ve published 13 books, most recently Little Panic: Dispatches From An Anxious Life. I sit on the advisory board of Bring Change to Mind and live in Brooklyn with my dog, Busy.

VITAL INFO:

All books sold through Bookshop provide me with a small commission. This small percentage contributes to the monthly costs of maintaining and running this newsletter.

📫 Missed last week’s newsletter? The End of Therapy.

💋 Don't keep How to Live a secret: Share this newsletter with other questioners.

❤️ New here? SUBSCRIBE!

😢 Want off? Unsubscribe here.

🙋🏻♀️ Email me if you have questions, comments, or topic ideas! [email protected]

Join the conversation